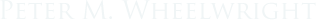

In his essay, The Origin of the Work of Art, the philosopher Martin Heidegger made an important distinction between the Earth and the World. Roughly, the “Earth” is the biotic entity that precedes humanity, and the “World” is what humans make of the earth when they show up on its surface. One might say the Earth is the back drop to the activities of the World, but it is not a passive back drop; there is turbulence. And it is in rivers where this turbulence between the natural earth and the cultural world is best captured. Rivers are where continents drain downstream to the sea and where continents were conquered by men sailing upstream from the sea. In my novel As It Is On Earth, the protagonist, Taylor Thatcher, feels he is still caught there, spinning in the vortex:

“…Everything eventually ends in the rivers, draining away to the sea, sediment settling into a deep abyss, our last stop. Far beneath Heaven…When the Androscoggin appeared in the distance, silver-white, glinting orange rays of low sun, I did not point it out. Nor did I mention again Esther’s matriarchal ancestors at the river’s edge, watching the clear continental waters that flowed to the ocean on the land’s descending slope and, then, the strange men – out of that same blue sea – holy fervor in tow, flowing right back upriver to the wellsprings. I could think only of my own mother, caught in the middle, spinning in the turbulence, the endless back and forth of living things, their death and decay. I could have said that everything also begins in the rivers. And in the feeble attempts to resist an expanding Universe’s slow crush toward the center of the earth.”