It is commonly remarked that major league baseball is an adult sport but a children’s game. I think this means different things to different people. You’d have to ask around. I would suggest this: the sport requires skill; the game requires imagination. Both require someone to play it with.

Only some children acquire the skill, but every kid who loves baseball has the imagination and it is usually because a particular major league team along with one of its players – The Favorite – has captured it.

At age eleven, my skill in the sport was so-so; however, my imagination in the game was vivid. And I had a best friend who shared this with me.

Childhood is a time of imaginative desire, scattershot and inchoate, feelings of longing for things that can be named even while

the feelings themselves remain beyond description. In short, a lot of baggage gets packed for the away games that adult life has in its schedule.

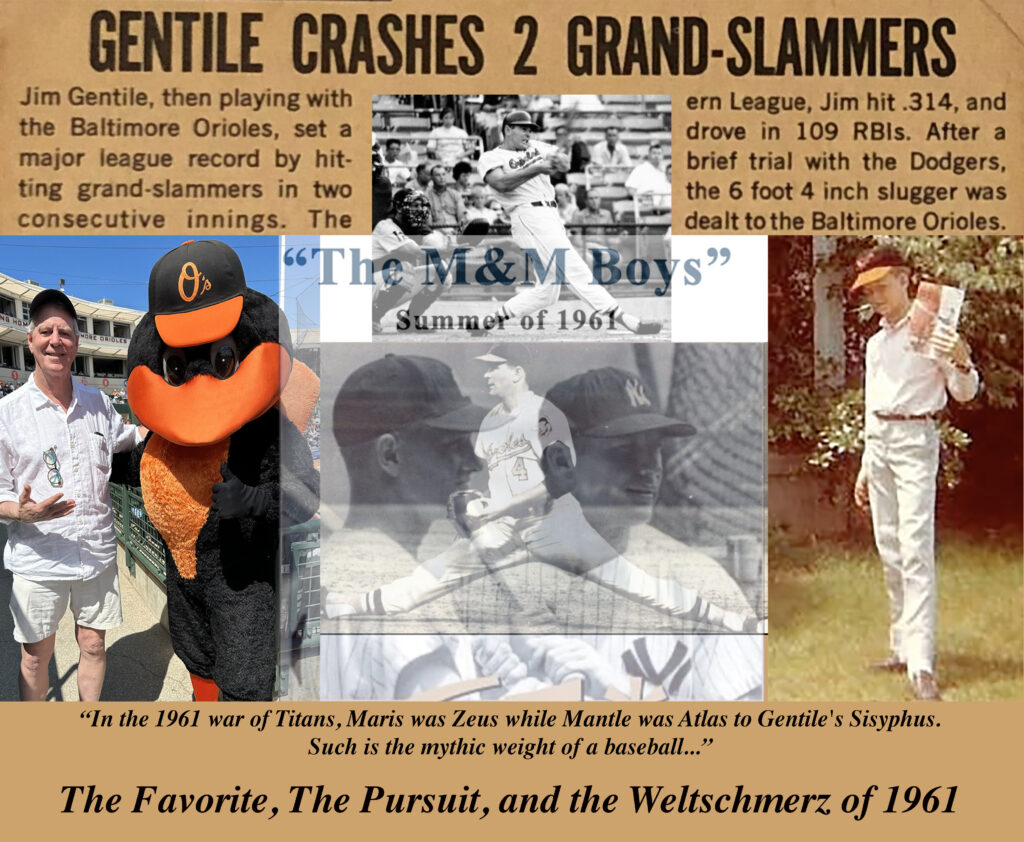

Such is the case with my childhood friend Earl and me. We are in our seventies now, living far from our original “fields of dreams.” But my car continues to sport a Baltimore Oriole decal; his, the interlocking letters of the New York Yankees. When asked about our favorite numbers, I answer: four, he answers: seven, only explaining the respective genealogies if our inquisitor is a fellow traveler – someone who would understand the existential significance of The Favorite. And, of course, it is only with Earl my childhood Yankee friend, that I can still share our differing anguish over The Favorite, The Pursuit, and The Weltschmerz of 1961.

My attachment to the Orioles can be pinned on a quirky babysitter with an unsettling glass eye that kept focus on both me and all things baseball. Living at the time in nearby Aberdeen, I was a four-year-old on her watch when Bill Veeck sold the St. Louis Browns to a Baltimore consortium in 1954. For the next few years, daycare was in the home of the Orioles at Memorial Stadium. I believe this is what psychologists call…Imprinting.

I left Baltimore and moved north with my family. The Orioles, by now virtual family members, migrated with me. And along with them came my Favorite – the Orioles’ new slugging first baseman, number four “Diamond” Jim Gentile. The Yankees and their stalwart center fielder, number seven Mickey Mantle were there to greet me – in the form of my new neighbor and soon-to-be best friend.

That summer, mornings of T-ball had long since given way to evenings of Little League. Our field was a small fenced-in wedge of grassy dirt where foul balls would come to earth only to rise again in a high bat-crack-sounding bounce off the streets flanking the first and third base lines. Rare home runs either disappeared through a rustle of thick leaves into the woods looming over the outfield fence or thwocked off a limb back onto the field with antiphonal mimicry. Nevertheless, in my mind’s eye that tiny suburban sweep of ballpark was Memorial Stadium in downtown Baltimore and I was body-snatched by James Edward Gentile.

To help flesh out my new incarnation, I had insisted on some tailoring to my little league uniform. My mother unstitched my given number and replaced it with Gentile’s number four, inscribing his nick-name beneath it. With black and orange permanent markers I rendered a poor copy of the Oriole ornithological emblem on both shoulders. And lastly, to the irritation of my coach, I had both sleeves cut off so I could exhibit skinny arm muscles that, in my imagination, were actually as prodigious as “Diamond” Jim’s.

And there were further adjustments.

Despite being a right-handed third baseman in an era when left-handers were considered better suited to first base, I crossed the infield. I mimicked Gentile’s batting style which required not only a vicious upper-body swing, but a locked front leg and ankle rolled outward in a painful corkscrew at home plate. Hitting a home run was less important than looking like I could. On the field, I worked tirelessly on “Diamond” Jim’s stretch to catch the ball ahead of the runner. Here, he was as graceful as a ballet dancer, with his right foot on the bag and left leg – heel to the ground, toes to the sky – extended in a grand jeté. I revered The Split as much as The Swing.

So, why did this former minor league journeyman in the Brooklyn Dodger organization capture my affections so thoroughly when he was traded to the Baltimore Orioles in late 1959 for $50,000 and two players “to be named later”…?

Who knows?…I guess that’s what I mean by imaginative desire. All I can say is that young fans of major league baseball are essentialists. The team closest to their heart has a nature – a glorious quality which can be sensed but not easily explained – and its essence is distilled in the glory of the one player who seems to embody it best.

In 1960, Gentile’s first year with the Orioles, he was named to the American League All-Star Team and, entering the last month of the season, he had helped carry the team to a small lead over the Yankees in the race for the American League Pennant. I was crestfallen when the Orioles succumbed to a final sixteen-game September swoon that dropped them into 2nd place behind the Bronx Bombers, but I was thrilled that the Bird’s new first baseman had led the team in Home Runs, Runs-Batted-Ins, Slugging and On-Base-Percentage.

I was certain that 1961 held even more promise; it would be our year – mine and “Diamond” Jim’s. My Yankee-Mantle-loving friend Earl felt the same way about his chances. Instead, for only slightly different reasons, it became the summer of our shared anguish. In hindsight, I should have seen it coming.

Gentile’s ascent from the minors to major league baseball had been blocked by the durable future Hall-of-Famer Gil Hodges whose grip on first base was unbreakable. However, the Dodger catcher Roy Campanella had considered Gentile exceptional and called him “a diamond in the rough” for the shape and brilliance of his slugging skills. Of such things are nicknames born. And my friend Earl knows this as well as anyone.

1960 was also Roger Maris’ first year with the Yankees. He’d come to them in a trade that sent Marv Thornberry, Hank Bauer, Don Larsen and Norm Siebern to the Kansas City Athletics. As if ordained by some mythic baseball trickster, all four of those ex-Yankees would later play their part in the woe that awaited me. That season, Maris won the American League MVP, edging out Mickey Mantle by 1% of the vote. And the following year, in a hegemonic assault on baseball imagination, the two men took on the sobriquet of the “M&M Boys.” It was a memorable moniker guaranteed to hook any kid with a sweet tooth.

I resisted. And, oddly enough, Earl surprised me with his own ambivalence. A kid’s Favorite is hard to dislodge but can be easily threatened. Wrapt for many of his young years in Mickey Mantle’s thrall, Earl was concerned that Roger Maris might obscure his lodestar. I was unsympathetic and equally unsuspecting that both Yankees would soon eclipse mine.

The 1961 season started well for “Diamond” Jim. In early May he broke a grand slam record by slugging two in consecutive at bats during a game against the Minnesota Twins, and by the end of the month he was ahead of Maris and one shy of Mantle’s lead in home runs. As for me, my avatar was holding his own in ferocious games of home run derby, whacking whiffle balls over the garage roof in “Mickey Mantle’s” driveway.

But by the end of June, Gentile had cooled off, Mantle was still hot, but Maris was on fire. There was talk of Babe Ruth’s Record. And, although “Diamond” Jim was within single digits on the home run leader board, the focus was zooming in on the “M&M Boys.”

As much as one loves their team, so too they must have one to hate – even if it’s their best friend’s. And just as one’s favorite player embodies all that is good with their team, there is a player (or players in this case) in the dugout of one’s nemesis who embodies the opposite ethos. I would call this the equilibrium of the baseball mystics where opposing divine forces meet in good-natured spiritual harmony.

But Earl was as put-out as I was over the pursuit of Ruth’s record. Not on behalf of my Favorite, but for his. If the Ruthian pursuit was going to be a Yankee thing, he believed that by the light of all the baseball gods it should be led by Number seven. In his eyes, the “M&M Boys” were Mantle and Maris, not Maris and Mantle.

By mid-July, The Pursuit was real. And it was serious. Gentile was still in the hunt, but Mantle had gone on a tear and now shared the lead with Maris at 36 HRs apiece. Earl was hopeful, I was disgruntled. “No wonder!” I would squeal at him, “Maris is hitting before Mantle, and he’s hitting in front of Berra, Howard and Blanchard, no one will ever walk him to get to those guys.”*

In the combined months of July and August, Jim Gentile hit more home runs than either Maris or Mantle with 25 HRs to Maris’ 24 and Mantle’s 23. Nevertheless, by September 1st, with just one month to play, it was Maris who led the home run race with 51, while Mantle stood at 48. Earl was feeling discouraged…but I, more so. With only 43 HRs, Gentile was clearly falling out of The Pursuit. And as the month wore on, it seemed to me he was falling off the face of the Earth while the “M&M Boys” were headlining every sports page around the world.

My Favorite had joined the Orioles’ tendency to swoon in September with his worst month at the plate – only three home runs and a .184 batting average. Earl’s Favorite was not faring much better. Mantle’s slump had a corporeal aspect to it – he could barely walk.

On Sept 26, Roger Maris tied Babe Ruth’s record with his 60th home run. I gnashed my teeth…the game was against the Orioles. By then, the roar of The Pursuit between the “M&M Boys” had become an exhausted whimper. Mantle, stuck at 54 HR, had only one at bat before leaving the game and entering the hospital the next day with an infected hip abscess, his regular season ended. And, as if to confirm his send-off to oblivion, Jim Gentile did not even play that day. When Maris broke Ruth’s record in the Yankee’s final game of the season, Mantle watched from his hospital bed, and Gentile was in mufti driving home for the winter.

Earl soon came to accept the collapse of his Favorite, taking consolation as the Yankees went on to win the American League crown and the World Series. Things would only get worse for me. The Orioles 3rd place finish mirrored Gentile’s 3rd place finish in the MVP voting. The award for Most Valuable Player had re-played The Pursuit. In neck and neck voting, Maris took home the gold with Mantle a close second. Jim Gentile was an after-thought at a very distant third.

It didn’t seem fair to me. Gentile had 100+ less at bats than Maris with a higher On-Base-Percentage, higher Slugging average and the higher On-Base-Plus-Slugging that came with it. His .302 batting average was 33 points higher and, even with 15 less HRs than Maris’ 61 dingers, he still drove in the same number of runs at 141 RBIs.

Earl went through a similar but less heated calculus on behalf of Mantle; however, as I said before, things would only get worse for me.

The late writer Walker Percy, who may or may not have been a baseball fan, once noted that “small, disconnected facts, if you take note of them, have a way of becoming connected.” I agree and here is where my vivid imagination conjures the mythic baseball trickster I mentioned earlier – the one who, seemingly on my behalf, orchestrated the Maris trade for the four players from the Kansas City Athletics in 1960. To wit:

(1) Marv Throneberry was traded from the Athletics to the Orioles in June of 1961. He was the one playing first base on September 26 as Gentile slumped in the dugout watching Ruth’s solitary hold on the HR record come to an end.

(2) Hank Bauer came to Orioles in 1963 as their new first-base coach. I did not like him because, for reasons still unknown to me, he apparently did not like my Favorite. At the end of the season on November 19, Bauer became the Orioles’ manager.

Eight days later…to my horror,

(3) Norm Siebern was traded to the Orioles in a one-for-one swap for “Diamond” Jim Gentile. Siebern was given Gentile’s number four; I threw out my little league uniform in a rage of tears.

(4) Don Larsen played a more benign role…as if gently nurturing me along. He pitched in two different seasons with the Orioles. His first, in 1954 when my glass-eyed babysitter began to brainwash me at Memorial Stadium, and his last in 1966 when Jim Gentile retired from professional baseball. I was resigned by then to “Diamond” Jim’s fate, and took further solace when Siebern was traded away, the Orioles won their first World Series, and Earl’s Yankees finished in last place.

Poor Earl, the next few years would not be kind to the Yankees.

By the way,…Earl is not my childhood friend’s real name. I’m not trying to protect his identity, and I know he will surely recognize himself if he ever reads this. I had something else in mind. Let’s just say that my Weltschmerz in 1961still prompts a bit of Schadenfreude teasing…after all, the Favorite of my fellow-traveling friend also lost out that year.

The Yankees retired Mickey Mantle’s number seven in 1969. My Yankee-Mantle-loving pal swelled with pride. But 1969 was also the first full year of the Orioles feisty new manager who would absolutely dominate the Yankees over the next six years and most other teams thereafter. When the Orioles retired the number four in 1982, it was not to honor my Favorite but to honor Earl Weaver who had taken Gentile’s number to a higher glory as the winningest manager in all of baseball during his time at the helm. I considered it a modest lagniappe tossed my way – at least no one else would ever wear the number again.

Today, every fan of the game knows of the “M&M Boys.” Few know of “Diamond” Jim Gentile. In the 1961 war of Titans, Maris was Zeus while Mantle was Atlas to Gentile’s Sisyphus. Such is the mythic weight of a baseball…in the game. In the sport, it’s something else entirely. Fortunately, “Earl” and I – the ones who still play the game – can still laugh about the difference.

* in 1961 Yogi Berra, Elston Howard, and John Blanchard – all originally catchers – combined for 64 HRs batting 5th behind Mantle. I suspect there is a record in there somewhere.